SMS text messages are a weak, dangerous way of providing two-factor authentication codes, as we discussed years ago in “Facebook Shows Why SMS Isn’t Ideal for Two-Factor Authentication” (19 February 2018). Unfortunately, even though the problems with SMS for 2FA are well-known, many companies and government organizations continue to use it. The problem is that, for most people, most of the time, it works. But I’ve just resolved a problem where SMS 2FA codes didn’t work, and it’s worth sharing in case you or someone else you know is experiencing a similar problem.

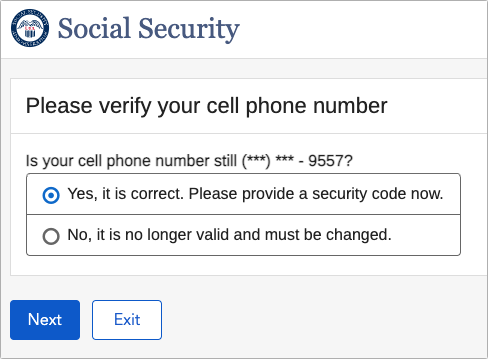

In August 2021, we switched from AT&T to T-Mobile, and it has been a highly positive move for the most part. At some point, however, I discovered that I couldn’t log in to my Social Security account because it needed me to enter a code texted to my cell phone number. Despite several tries over a few days, the code never arrived on my iPhone. Since I have no near-term plans to retire and all other SMS text messages were arriving properly, it wasn’t worth my time to figure out why.

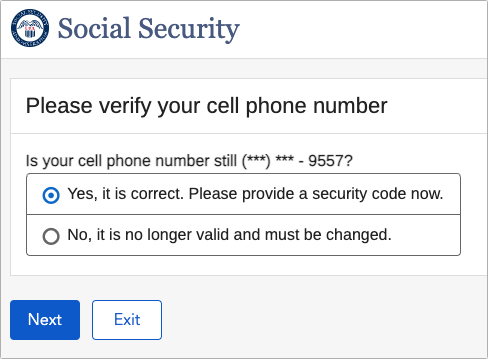

A while later, I needed to log into the Finger Lakes Runners Club QuickBooks Online account, which also had an SMS-mediated login verification. That failed in the same way—the text message never arrived—but I was able to work around the problem by falling back to email. Although QuickBooks Online now offers app-based 2FA, turning it on requires being able to receive a text message first.

The problems continued. I couldn’t turn on 2FA with a site called TaxCaddy that our accountant uses for transferring and tracking tax-related documents. The local credit union website we use for online banking wanted to send me a text message for some reason, but it never arrived—it was no great loss because I had to use Tonya’s account anyway (and she never experienced any problems receiving 2FA codes). The straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back was another local bank’s website. It would let me log in and do most things but required an SMS 2FA code for making admin-level changes to users, which I needed so I could increase the amount my account could transfer between accounts.

So I called T-Mobile and explained my situation to the customer service rep. She understood the problem instantly and said she would remove the necessary block on my account. It took seconds, and as soon as she did it, I was able to verify that several of the previously blocked accounts could now send me text messages.

Why had this happened? The rep couldn’t say for sure, but it was likely associated with T-Mobile’s efforts to block scams. Most of those are voice-related, but apparently, they can also result in text messages being blocked. In other words, it’s an opaque system, and there’s no way of knowing exactly what happened. The commonality among the five websites I’d recorded as having troubles was that they all provided financial services. It seems odd that T-Mobile would block them, particularly government outfits like Social Security, but on the other hand, scammers might try to spoof text messages from such sites.

All’s well that ends well, but the moral of the story is that if you aren’t receiving SMS text messages, particularly those that carry 2FA codes, call your cellular carrier and ask if they’re being blocked.

Every week you’ll get tech tips, in-depth reviews, and insightful news analysis for discerning Apple users. For over 33 years, we’ve published professional, member-supported tech journalism that makes you smarter.

Registration confirmation will be emailed to you.

Thank you for those word of caution, @ace.

Just one question for you to answer in the future: will you notice an increase in the amount of SMS spam you receive on that number?

I have two problems with SMS 2FA.

Your first point is a problem with 2FA in general, not just SMS 2FA. Only a relative handful of people use dedicated 2FA hardware, and those are generally among the most tech-savvy people anyway (and thus are almost guaranteed to have cellphones). The rest of us use SMS or 2FA apps. So not having a cellphone at all pretty much locks you out of using 2FA altogether. Therefore, not a big concern regarding SMS 2FA specifically.

The second problem can be resolved by using a WiFi access point with a carrier’s cell-service-over-WiFi feature (such as Verizon’s WiFi Calling). This routes cell-network signals through a connected WiFi network if a cell signal is unavailable (or preferentially, if you have it set that way). This isn’t for data, which is Internet anyway, but for voice and text, which by default are not sent over the Internet. I wouldn’t recommend using it to receive an SMS 2FA code via a public hotspot, but with a trusted home network, it’s a reasonably secure option.

The fundamental problem with SMS 2FA, as Adam has pointed out before, is that phone numbers are relatively easy to steal these days. If someone clones your SIM, they’ve got full access to anything you subsequently receive over SMS. But it doesn’t grant them access to your apps, keeping things like Google Authenticator safe from this particular exploit. So security, not lack of access, is SMS 2FA’s Achilles’ heel.

The fundamental problem with SMS 2FA, as Adam has pointed out before, is that phone numbers are relatively easy to steal these days.

I believe this is really primarily an American thing. None of the European countries I spent time in would allow you to order a new SIM without showing up with some form of government issued photo ID or further verification. This thing that some twerp can call up a cell provider, pass on a ZIP code as “authentication” and then have a SIM shipped to some shady PO Box seems to be a distinctly American issue. What I’m getting at is this is a choice we seem to have made somewhere along the way. Others appear to have made better choices. Perhaps we need to revisit this issue and reconsider if sacrificing security for convenience is really the right call when we rely on this conduit for such sensitive matters such as authentication. That said, I’m not trying to argue for SMS 2FA. I just think it doesn’t have to be as crummy as we have made here in the States.

First, believe it or not, not everyone has a cellphone

Some service providers (e.g. Google) give you the option to receive an SMS code via a voice call. Of course, if you don’t have a mobile phone, you’ll need to be near your land line in order to receive it.

The rest of us use SMS or 2FA apps. So not having a cellphone at all pretty much locks you out of using 2FA altogether.

I’m actually surprised that we don’t see desktop apps for generating TOTP authentication codes. The algorithms are industry-standard (RFC 6238), and there are open source libraries that implement them. But it seems to be rather hard to find a desktop app to present it in a friendly way, the way many apps do on mobile platforms.

Regarding 2FA, there are other alternatives. But they’re not as widely used on the Internet:

A TOTP authentication code using a proprietary algorithm. Apple’s iCloud authentication is one. (Note that the codes presented on a phone, iPad or Mac are locally generated, not received from the server. You can also manually request codes.)

Voice call. Google supports this, as do some banks. You still need to be near the phone that will ring when the registered phone number is called, but you don’t need to be able to receive text messages.

Paper codes. Google lets you generate 10 “emergency” single-use OTP codes that you can print and keep with you, for when you have no other means available. But I haven’t seen anybody else support this. Of course, if you use this as your primary mechanism, then you must make sure to generate/print more as you use them up.

I believe this is really primarily an American thing. None of the European countries I spent time in would allow you to order a new SIM without showing up with some form of government issued photo ID or further verification.

All of the major US carriers have similar policies, but unfortunately there are many recorded incidents where customer service personnel were convinced to violate policy in response to a suitably convincing sob story (or sometimes outright bribery). Even when the owner of the account enabled all of the extra optional security features designed to prevent this.

Customer service staff have lost their jobs over this, but it doesn’t do you a whole lot of good if you’re the person who got victimized.

Authy is available as a desktop app, it will sync alongside phone/tablet/etc versions.

Good to know about Authy.

I forgot to mention an additional alternative for receiving SMS when you have poor cell connectivity: iMessage. If you have an iPhone and a Mac, you can connect your Mac’s Messages app to your iPhone through your Apple ID, and thereby receive your SMS messages on your Mac via iMessage regardless of cell connectivity, as long as you have an Internet connection.

I’ve been doing this since my first iPhone, and it makes using 2FA codes on my Mac so much easier (just copy and paste). It also means that I don’t have to pick up my phone every time I get a text while I’m working.

I forgot to mention an additional alternative for receiving SMS when you have poor cell connectivity: iMessage. If you have an iPhone and a Mac, you can connect your Mac’s Messages app to your iPhone through your Apple ID, and thereby receive your SMS messages on your Mac via iMessage regardless of cell connectivity, as long as you have an Internet connection.

I don’t see how that can work if you don’t have cell coverage at all. An SMS is sent over the cellular network. It only gets displayed alongside iMessages in the Messages app, but it still remains an SMS. If cell coverage goes away, there is no SMS traffic. Your Mac can use an attached iPhone to receive and send SMS, but when doing so it still relies on the iPhone being able to connect to the cellular network. If you have cell service over wifi, wifi can effectively “extend” cell coverage even outside of the provider’s usual coverage area, but ultimately that message will always come in as an SMS over the cellular carrier’s network. If that goes away, there is no more SMS traffic.

For this to serve as a truly independent alternative, you’d have to be able to choose to receive 2FA codes as iMessage instead of SMS. That way all you’d need is a data connection, possibly through wifi or Ethernet, independent of cell coverage. I’m not aware any company I do business with offers to send iMessage instead of SMS.

And BTW, Authenticator exists as a desktop app on the Mac. It’s on the MAS. It can sync over iCloud with your iPhone etc. (if you get the paid version that is).

Just one question for you to answer in the future: will you notice an increase in the amount of SMS spam you receive on that number?

I’d be surprised given how few websites/numbers were affected by the block, but I’ll certainly keep an eye out. I get almost no spam now, if you don’t count all the political candidates.

None of the European countries I spent time in would allow you to order a new SIM without showing up with some form of government issued photo ID or further verification.

I have very little experience in Europe, but it does seem to be an issue there, if this article is an indication.

European authorities managed to crack down on two cybercrime gangs responsible for stealing millions by employing SIM hijacking

You may be right about needing the cell network to get the SMS via iMessage in the first place. I’ve never tested it without my cell phone being nearby and on.

I will mention, though, that I have occasionally flaky cell service where I am, and I have occasionally received a notification for an SMS message on my Mac, but the phone doesn’t show it until after a distinct delay. (Not the notification, but the message itself not showing right away on the phone. Sometimes I’ll see the notification on my Mac and choose to view the message on my phone.) From that, I guess I assumed that the phone didn’t need to receive the message first, but those occurrences may have been due to a device issue (like most people, I don’t reboot my phone nearly as often as I should)—the phone got and relayed the message, but the iOS Messages app didn’t display it.

I have occasionally flaky cell service where I am, and I have occasionally received a notification for an SMS message on my Mac, but the phone doesn’t show it until after a distinct delay. (Not the notification, but the message itself not showing right away on the phone. Sometimes I’ll see the notification on my Mac and choose to view the message on my phone.)

Interesting. And this SMS (green-bubble message)?

I don’t know what’s going on, but here’s my (hopefully educated) guess.

SMS is a very low-bandwidth protocol. In its simplest form (just short bits of text with no attachments), it is just some data that piggybacks on the signaling protocols used to create virtual circuits (like those used to connect voice calls).

I could easily see a situation where the network quality is too poor to establish a connection (no voice calls, no data, zero bars), but there is enough for SMS to slip through. Possibly in bits and pieces as the network attempts to retry delivery over time.

In a situation like this, the phone might see the start of a message (including its caller ID) and assume that more is to come, and therefore generate the notification at that point. Then when the rest of the data eventually arrives, it can present the rest.

But this is just a theory. I don’t know nearly enough about the details of mobile phone networks to be sure about this.

Received messages don’t show green or blue, only sent messages.

But I know they’re SMS. The ones this usually happens with are automated notifications from businesses or medical providers—those systems are never going to be iMessage unless Apple opens the protocol outside of Apple devices. It’s usually the lengthy messages with lots of unnecessary boilerplate text, too. That may have something to do with it.

Thanks Adam, this is a helpful writeup.

When doing some Bitcoin experiments in 2018 I ran into a similar 2FA surprise. At that time many of the sites one used for mining wanted or demanded 2FA and encouraged use of Google Authenticator. You muddled through and soon had multiple accounts with 2FA on various sites but now dependent on password + Google Authenticator. When I got a new iPhone and migrated via iTunes backup and restore Google Authenticator lost its configuration, broke and I hadn’t written down the original seed on paper needed to get it working again with all my Bitcoin related 2FA sites. Some of the sites had a 2FA lost equivalent of password recovery and others had to be abandoned.

As you correctly note some institutions embrace 2FA and its great “when it works” without an appreciation for the fragility it introduces. They pass some regulators “we are more secure” checkbox by adding 2FA without an appreciation of failure modes and process to deal with them.

When I got a new iPhone and migrated via iTunes backup and restore Google Authenticator lost its configuration

That’s really annoying. The lesson here (for those of us who might need to do this in the future) is to make sure everything migrates correctly before wiping the old phone. And try a second time if it doesn’t work the first time.

FWIW, when I migrated from an iPhone 6 to a 13, using direct device-to-device migration, my Authenticator codes all migrated OK.

It’s also worth noting that the current version of Authenticator has a feature that will let you export some or all of your keys to a QR code, which can be used to import them into another device. But I don’t think this feature was in the app in 2018.

(And, FWIW, after writing this, I decided to generate that QR code and print a copy to keep in my file cabinet, for emergency recovery.)

That’s indeed fine advice if you’re just migrating from an older iPhone to newer. But folks who are moving to a newer iPhone after they perhaps lost theirs or it got destroyed need to be able to rely on migration from backup working out 100% irrespective of the state of the old iPhone.

It would be nice to know Apple and app manufacturers keep that in mind when they design their backup/sync tools and strategies. In my personal experience, the last migration in 2020 to a 12 mini from an SE worked well, but Google Authenticator (that my employer forces upon us) was one of the few holdouts that had to be set up from scratch despite iCloud drive in principle being available to the app for backing up. On my main work Mac I use Authenticator App for this Google authentication stuff and that app (in its paid version) actually backs up to iCloud drive so that you can always recover, but also such that you can have it sync to all your other Macs and iDevices. Haven’t had to rely on that so far (and hence no personal experience actually testing that feature), but sure sounds very handy to me.

And this is why you use something like Authy that is distributed across various devices…

That was my driver for moving years ago because the Google implantation didn’t support multi-device/transfer etc. in a sane manner.

If your company insists you use a broken authenticator I am not sure why you get to blame Apple for that, just use a sane one that works for everywhere else. However as an open standard it is quite hard to insist that you must use a particular implementation other than by corporate policy and discipline.

I hadn’t thought about it but for some 2FA actions on my Mac the Mac receives the code and prompts me to use it to fill in the field. This happens with Apple services but also some others.

This is convenient as I don’t have to go searching for my phone but, on the other hand, it seems to defeat the purpose of 2FA since the device that is requesting the 2FA is the same as the device providing the code.

In any case, I agree that 2FA via SMS is lazy security on the part of service providers.

One of my banks uses an iOS security app called VIP Access that seems more secure. It is a little taxing for us, however, as it gives you just 30 seconds to read and enter the code. Also I found out that it is locked to a particular phone and to change phones it needs to be deauthorised on the old phone (if available!) and authorised on the new one.

2FA (at least these days) doesn’t hinge on requiring two separate devices. It requires something you know (user/password) plus something you have (device). That way if somebody gets one, they still can’t get in without also obtaining the other.

I very seldom use text messages at all. I usually do log-ins from my iMac so if I have the option, I use email OR a phone call. In addition even though my home phone is labeled HOME and not CELL, some sites want to send texts to my home phone!

Oh another bugaboo (primarily from Apple) is when I go to log in from Safari, they want to send me a code to verify a new browser. After entering the code I’m asked if I want them to trust my browser, and I say “yes”. So the next time I log in from the same iMac running the same MacOS version and using the same Safari version, I often get the same demand to verify “a new browser”!

Re “verify the new browser”: yep it’s happened to me multiple times, too. Although if I’m not mistaken, the occurrence seems to be site-specific? ![]()

Although if I’m not mistaken, the occurrence seems to be site-specific?

Yes, and for me that specific site is various pages of apple.com!

Alas for me it’s usually some public utilities ![]()

connect your Mac’s Messages app to your iPhone through your Apple ID, and thereby receive your SMS messages on your Mac via iMessage

Interestingly I used to see this work fine, and for some reason a few months ago it stopped. 2FA messages come through fine on my phone, but won’t come through on the Mac via Messages.

Your phone must be configured to forward SMS to/from your Mac. And both phone and Mac must be signed in to the same Apple ID.

Set up your iPhone so you can get SMS text messages on your Mac, as long as your iPhone and Mac are signed in using the same Apple ID.

I experience the same thing. I’ve always assumed it was part of Apple’s “Intelligent Tracking Prevention” deleting local storage databases every seven days (if you haven’t visited the specific web site during that time). This began with the release of Safari 13.1 in early 2020. One article describing the issue and its unintended consequences is from IT News:

https://www.itnews.com.au/news/apple-cops-flak-for-deleting-local-browser-storage-after-7-days-539833

Later releases of Safari may have expanded on these privacy protections affecting even more site’s “memory detention” data.

Your phone must be configured to forward SMS to/from your Mac. And both phone and Mac must be signed in to the same Apple ID.

Yup, it’s set up for getting SMS. All my other messages get through fine, it’s only the 2FA messages that don’t.

Strange indeed. It seems as if Apple is explicitly looking for and filtering out those messages. Maybe a security feature (so someone with access to your Mac can’t access the 2FA codes without also having your phone)?

I wonder if this situation explains some of the blocks you experienced.

Texting voters just got harder, right before the midterms.

I don’t see how that can work if you don’t have cell coverage at all. An SMS is sent over the cellular network. It only gets displayed alongside iMessages in the Messages app, but it still remains an SMS. If cell coverage goes away, there is no SMS traffic.

Is that true?

I thought Apple was able to terminate your incoming SMS messages and relay them into their iMessage network, in which case you could receive them over WiFi. But I should test this.

I could easily see a situation where the network quality is too poor to establish a connection (no voice calls, no data, zero bars), but there is enough for SMS to slip through. Possibly in bits and pieces as the network attempts to retry delivery over time.

I’ve had enough experience camping to see this behavior. Small messages like sms sometimes could succeed where mms or other things could not.

Is that true?

Yes – Apple doesn’t run SMS relays for this feature. Your iPhone is the SMS relay, and if it can’t receive the SMS, then the text won’t appear on your Mac.

Thinking about how it could work, I can’t even see how Apple could run SMS relays for this feature. They would somehow need to be able to take control of the routing for any mobile number on any network in the world, without agreement or a relationship with the carrier.

Thinking about how it could work, I can’t even see how Apple could run SMS relays for this feature. They would somehow need to be able to take control of the routing for any mobile number on any network in the world, without agreement or a relationship with the carrier.

It’s just software. There might be something in the iMessage EULA where you give Apple relay control over your SMS and then they take care of configuring that hop with Neustar or whomever and all the carriers dip that db when figuring out how to route such messages.

I should probably do a test to convince myself ![]()

Is that true?

It is.

Your Mac doesn’t have any cellular capablities. It’s all provided by your iPhone. Apple certainly cannot inject themselves into your carrier’s SMS routing. Well perhaps they could in theory, but then they’d have to negotiate a deal with each and every cell provider worldwide (and what would their incentive be? why let a potential competitor inject themselves into your network?) and we’d certainly have heard about that.

No, it all happens app-side when they combine SMS and iMessage in Messages so they appear as if they came through a single unified conduit. Case in point, those SMS you receive send have a green bubble. You only get blue for actual iMessages. And gray background for this new corporate thing Apple has where they basically give companies a conduit to communicate with people through the iMessage network, but that’s unrelated to SMS. Again, just Messages making it look like they’re the same thing (apart from bubble color of course).

That SMS come through even when you see essentially zero data b/w or no voice coverage, is a feature of GSM (not technically related but similar is that you at times will succeed in placing a 911 call even when you otherwise can’t get or place any calls), it has nothing to do with receiving them on an iPhone or a connected Mac (via relay).

But don’t take my word for it, just do the experiment. Turn your iPhone off. Then have somebody on an Android send you an SMS. I guarantee your Mac won’t get it until you turn your iPhone back on. And when you reply to that it will be as a green bubble.

Case in point, those SMS you receive have a green bubble. You only get blue for actual iMessages.

I hate to be pedantic, but received messages are always light gray bubbles. It’s your sent messages that are either blue (if delivered using iMessage) or green (if delivered using SMS/MMS).

No no, you’re absolutely right. Color only on outgoing. Fixed. Thanks. ![]()

I sort of blame Craig Federighi for this confusion. In one Apple keynote, he talked about “green bubble friends” and “blue bubble friends,” and since then, I’ve had to remind myself that the other person or people are gray, whereas you’re green or blue. It makes more sense to me that the color should clarify a fact about the other person, not you.

When I need to get a password / log in to someone I first message them a “Hello this is me is this you?” The color of the buble tells me if I can securely send the information via messaging.

Two points:

You don’t need to send a message to see how it will be sent. When you start typing a name, the drop-down list will color the matches in green or blue depending on whether sending to that address will be via SMS or iMessage.

What works for one message may not work for the next. If the recipient is having network problems, your phone may fail-over from iMessage to SMS, even if there have been previous SMS messages.

I used to see this all the time with my daughter, back when we had metered data plans on our phones (and she would therefore turn off cellular data most of the time to avoid hitting her cap). Depending on whether she was on a Wi-Fi network or not would determine how my messages got sent.

Of course, if you’re sending the test message immediately before the real message (and you wait for the “Delivered” status on the test message), then it will probably work OK.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

TidBITS is copyright © 2023 TidBITS Publishing Inc. Reuse governed by Creative Commons License.