Advertisement

Supported by

Beyond the crossword

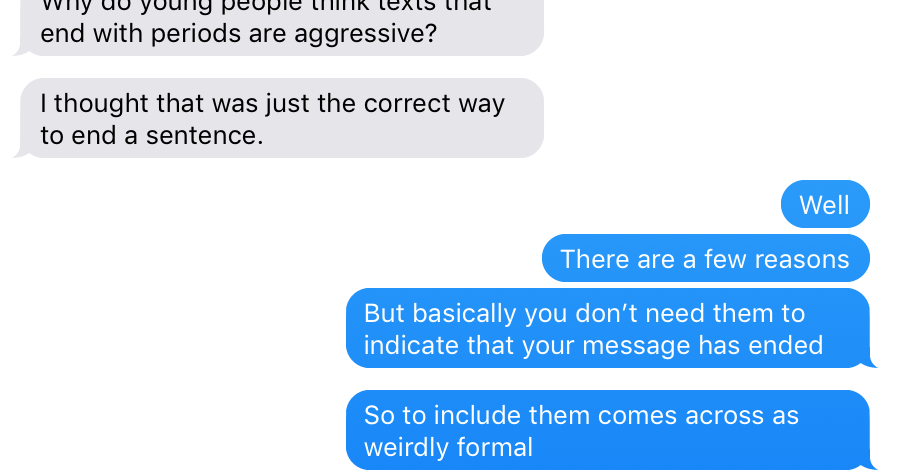

To younger people, putting a period at the end of a casually written thought could mean that you’re raring for a fight.

You’re out with a few friends after a long day at the (Zoom) office. You’ve been presenting a professional version of yourself for eight hours and are so relieved to speak freely at last, with as much slang and intonation and irony as you like. Then another friend joins your group and sits with perfect posture, contributing humorless and grammatically impeccable sentences to the conversation. Are you at ease? Or is this person kind of rubbing you the wrong way?

If you can imagine yourself in this situation, then you can understand how many young people feel when they receive a text buttoned up with a big, authoritative period.

To younger generations, using proper punctuation in a casual context like texting can give an impression of formality that borders on rudeness, as if the texter is not comfortable enough with the texting partner to relax. The message-ending period establishes a certain distance. The punctuation is polite when speaking to someone older than you or above you at work, but off-putting among friends.

Simply put, the inclusion of a formality in casual communication is unnerving.

Think of a mother using her son’s full name when issuing a stern ultimatum. Or of an upset lover speaking to a partner in a cool, professional tone, withholding intimate silliness and warmth to convey frustration. People gain and express interpersonal comfort through unpolished self-presentation, and acting (or writing) too formally comes off as cold, distant, or passive-aggressive.

It’s also worth noting that more of our casual communication is digital now than ever before, so texting etiquette carries at least as much weight as speaking tone.

Some experts, such as John McWhorter, the “Lexicon Valley” podcast host, can attest to the fact that, just as rehearsed speeches are analogous to formal writing, casual speaking is analogous to texting.

The linguists Naomi Baron and Rich Ling concluded in a 2007 study that “the act of sending a message coincides with sentence-final punctuation.” Using “text speak” has also been analyzed as a form of situational code switching. In other words, not using periods is a way for texters to indicate that they’re feeling relaxed with the recipient.

Gretchen McCulloch, the Canadian linguist and author of “Because internet,” dedicated an entire chapter of her book to “typographical tone of voice,” which explores not only periods and ellipses as signifiers of tone, but also TYPING IN ALL CAPS, which is seen as yelling; using *asterisks* and ~tildes~ for emphasis; the all lowercase “minimalist typography,” which can indicate a kind of deadpan, sarcastic monotone; and, of course, tYp1nG l1k3 th!z. (This is called “l33t [elite] speak,” and while it was once a sincere and popular way of spicing up texts, it is now employed almost exclusively in irony.)

The consensus is that many texters, especially young people, see end-of-message periods as tonally significant because they are unnecessary. It is clear that a message has ended regardless of punctuation, because each message is in its own bubble. Thus, the message break has become the default full-stop.

This pressure to get one’s thoughts across is intensified when correspondents are aware that the people they’re texting know they’re typing — as with speech, there’s a rhythm that both parties in the conversation are responsible for maintaining. To avoid keeping their pals in suspense, therefore, texters send out single, often unpunctuated phrases rather than full sentences.

Ms. McCulloch recognizes that adapting to this new convention may be difficult for older texters.

“There’s a tendency for people to believe that the rules they learned in school are fixed and unchangeable and everything after that is a barbarism, but that’s not how society works,” Ms. McCulloch said. “The fashions are different from when you were in school, words are different, and punctuation can be different too.”

The period’s “new” significance has been around for a while — The Washington Post, NPR, The New York Times and many others have written about the phenomenon in the last decade, most of them in the last three years.

With the period established as a signifier of seriousness in texts, other kinds of writing may have started to use it as such too. The period may have started to signify tone in social media posts and even online headlines, which have started employing more periods in recent years.

This is not the first time writers have repurposed standard punctuation. Even though each generation would like to think that it is the arbiter of style, the new conventions surrounding the period are just one episode in a centuries-long history of grammatical exploration.

Experiments with punctuation began long before cellphones or the internet. Consider postcards, in which the dash was employed to indicate the kind of self-interruption that happens when one thought runs into another and the ellipsis conveyed a casual trailing off.

The lexicographer and language columnist Ben Zimmer said the author Tom Wolfe’s effusive use of the exclamation point was one example, and framed it as part of a general loosening of rules during the counterculture of the 1960s.

Ms. McCulloch pointed to even earlier reference points: James Joyce’s 1922 classic “Ulysses,” and the poems of E.E. Cummings. The final chapter of “Ulysses” is a 40-page stream of one character’s uninterrupted private thoughts, punctuated by only two periods. Cummings’s poems play with words and punctuation to create an emotional atmosphere, rather than to be simply correct.

“They have this stylized kind of incoherence that conveys this very particular impression even though the words themselves don’t quite make sense,” Ms. McCulloch said.

These writers were experimenting and their language was explicitly artful, unlike most text messages. Authors such as bell hooks, of course, contribute more directly to this literary tradition than the average teenager with a smartphone. But the writers’ “lawless” usage (or omission) of punctuation demonstrates that people have long looked beyond grammar rules when trying to represent organic thought, speech, or feeling in writing.

Long story short, the so-called rules of punctuation are not preserved, lifeless, as if in amber.

Mr. Zimmer pointed out that style guides are constantly responding to changing norms. “Email” has become “email,” and “Internet” has also evolved to the lowercase “internet.” Just last year, the elderly became “older adults” in The Associated Press’s style.

“Something like the use of the period has clearly changed a lot just in our lifetime, and it is the type of thing that can spread from one medium to another,” Mr. Zimmer said. “I’m probably still relatively conservative when it comes to dropping periods, but I realized that I’m doing that more and more, which suggests that it’s becoming an expectation or a convention or a norm that people are now adjusting to, even older people like me.”

So when will newspapers’ style guides embrace the tonal significance of a period in a headline? Don’t hold your breath — the road from texting convention to official guideline is long. But in the meantime, texters can heed the German theorist Theodor Adorno’s advice when deciding how to close out a message:

“In every punctuation mark thoughtfully avoided, writing pays homage to the sound it suppresses.”

In other words, leave the period out if you don’t want to end up the subject of an unpunctuated text exchange among your friends.

Max Harrison-Caldwell lives in San Francisco and writes mostly about local news.

Advertisement

No More Periods in Texting. Period. – The New York Times